Grenades, Arrests and Lost Eyes: Stories from Rugby Folklore

French football is feeling sorry for itself after it left empty-handed from Qatar. So let’s look elsewhere – to the rugby pitch instead.

I’ve always found rugby as a whole rather loathsome and I’ve tended to make a conscious decision to avoid it. But international rugby… now that’s a different story. Whether it is the romance of playing for one’s country, the majesty or the tradition of international rugby that has always sparked my interest, I can’t be certain. But I always seem drawn to the international game over anything else. It could even go back to my youth to when I saw French No 8 Sebastian Chabal, ominously coined ‘The Caveman’, walk out of Waitrose with a baguette under his arm (true story).

It's also strangely intriguing to see 6-foot goliaths of men who could probably make concrete crack with just a glance, already bruised, bandaged and beaten visibly crying as they sing their national anthems. Whether it’s the Italians in 2011, the French bellowing La Marseilles at the Stade de France or the Kiwi’s and their Haka. As the spindly bed-wetting cameraman just fresh out of media college pans his camera across the team of maneaters and hellraisers of the XV – the audience are gifted the scene of these minotaur’s half man, half bull simply bursting with every sinew, locked into partnership with their fellow comrade flanked on either shoulder as the line they’ve formed in front of adoring fans swerves and weaves with every chorus, every screech, every bellow. It truly is a majestic sight.

The personalities who pen such acts of sporting majesty tend to be found – dare I say - more in the game of international rugby than international football. At least nowadays that is. The pruned hairstyles of the footballing elite whose legs are as weak as feathers – until suddenly they’re not again really don’t leave a very enduring or endearing image in one’s mind. It’s at this point that the footballer plods up to the journalist post-game and reads from the prosaic footballers hymn sheet.

“The most important thing is the three points and now we just need to focus on the next game”. Yes, I know you’ve just won the game I’ve been watching it for the last 90 minutes and frankly my interest is waning by this point Mr Footballer.

It seems the individual personality of the sportsman has been muffled in recent years. The clingy PR vultures have done well to pick off the carcass of the modern-day footballer. So we must turn to history if we are to find the heroic stories of sports past. More specifically, we must flick through that immensely thick and weighty book, with sepia-stained pages encased in a wine-red tumbled leather casing entitled ‘The History of Rugby’.

Now in my case, I might have to blow all the dust off the cover before I read through it, for I only pick up this book when the World Cup’s on or when I come across a story like this one.

International rugby also tends to attract some heroic nutcases. The sorts whose stories are whispered down from generation to generation. Ones that stalk the walls of rugby club houses decades later.

Figures like Paddy Mayne. Now shot to fame through the SAS: Rogue Heroes series which will sadly render him into nothing more than just a television character.

But before he was played by Jack O’Connell in the BBC show he was the cavalier commander of the SAS. Heavy drinker, ruthless soldier, merchant of death for the Axis airfields in North Africa, nominated for a Victoria Cross (its widely believed he was deprived of the VC because of his attachment to the SAS) and recipient of France’s highest award for merit, the Légion d’Honneur. Oh… and Irish and Lions international – capped 9 times for the Clovers and 20 for the Lions.

His drinking complimented his larger-than-life personality. One on drunken desert escapade, he once went out looking for the BBC’s Richard Dimbleby, Mayne apparently enraged by the cosy environment that wartime journalists were reporting their dispatches from when Mayne and his men were doing the real graft.

Another tirade follows that Mayne shot the floor around a barman’s feet after he made the mistake of overcharging Mayne. He also used to play tricks on his comrades at the dinner table – placing a grenade on the table and pulling out the pin. Sitting their unmoved until he relieved his men that it was indeed a dud.

A car crash in 1955 after a night of heavy drinking was the only thing that could finish him off. By their very nature, people like Paddy Mayne do not die in bed. Their flags remain flying over the many battlefields on which they bore their name – to the very end.

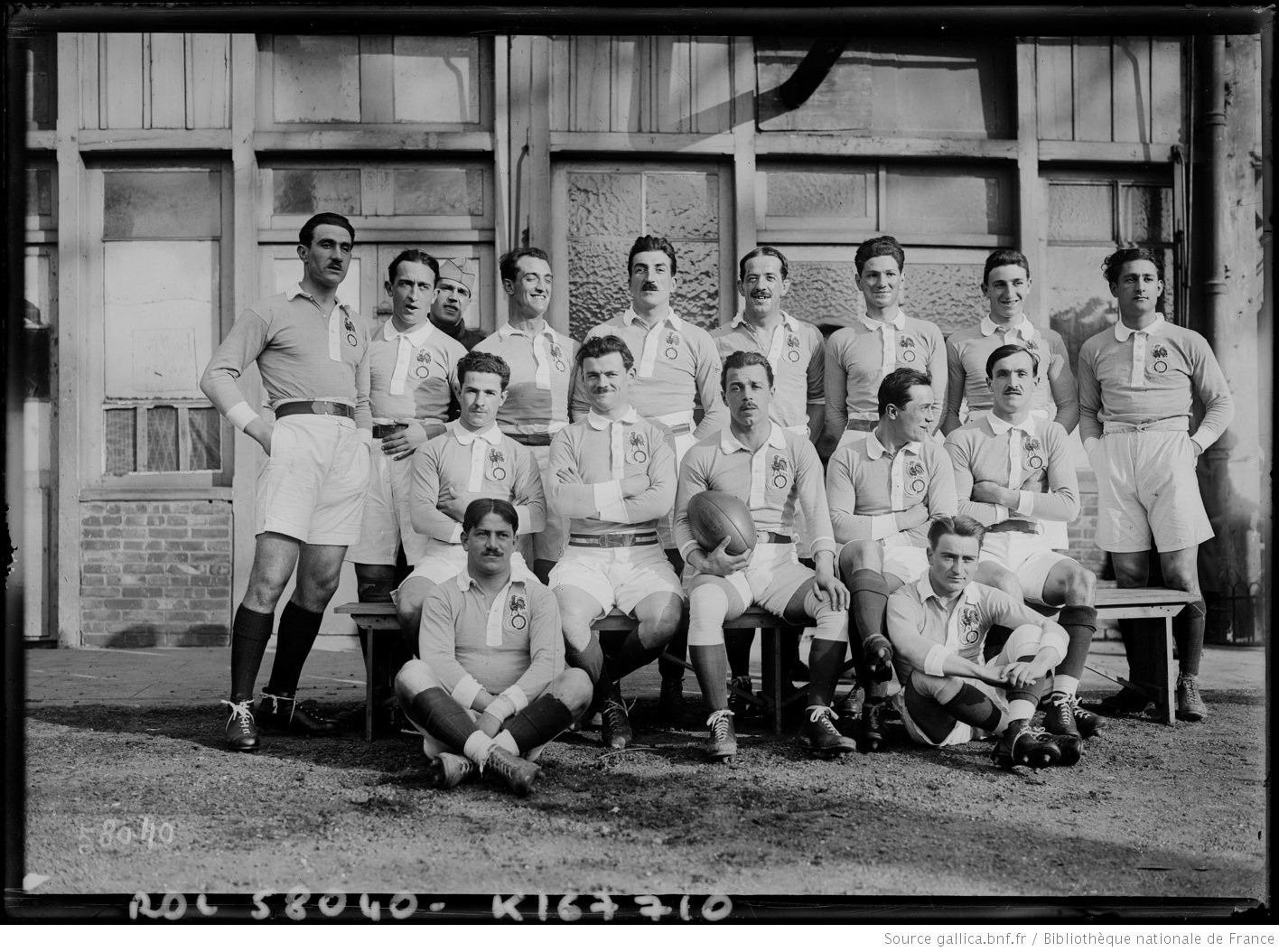

Now, this story starts not in the desert under Rommel’s bombs like the story of Mayne. But with a rugby jersey that I bought a couple months ago. It was a remake of a 1920 French rugby jersey with the French rooster wings outspread sitting proud on the chest under two rings. That was the logo of the French sporting corps from 1892 until the 1920s. The rings representing the USFA (Union des Sociétés Français de Sports Athlétiques) – the governing body of French sport at the time.

But this jersey is much more than just another example of French sartorial prowess. The shirt was worn at the 1920 Five Nations and worn by one man who could strike fear into the hearts of opponents and of journalists having to spell his name in the post-match report. Marcel-Frédéric Lubin-Lebrère.

Lubin-Lebrère was a man similar in stature and legend as Paddy Mayne. And has become revered in his hometown of Toulouse, even becoming Mayor of the city after his playing days.

He and his fellow players were to play in the first international rugby game following the First World War – a game that was grimly given the nickname of ‘Les Match Des Borgnes’ or the match of the one-eyed played between France and Scotland at the Parc des Princes.

It was given this nickname because five players – including Lubin-Lebrère – had lost an eye in the conflict.

Predictably, the war was not kind to rugby. It was reported that the French team lost 23 of its 111 pre-war internationals. Yet Lubin-Lebrère was not one of them – but only just. The Toulouse prop was the lone survivor from the squad France put out for their last fixture before the war.

Lubin-Lebrère was left for dead in the Somme, ridden with 23 shrapnel holes and shot 14 times. Toulouse fell into mourning – assuming they had lost their collective son. Instead he was being cared for in a German POW camp. The only thing he left behind on the battlefield was his right eye.

But that was not all in the Lubin-Lebrère story. At the 1921 Five Nations – France were to play Ireland in Dublin. The night before the game – always up for a merry time pre-match - Lubin-Lebrère and a few teammates found themselves in a pub in Dublin. It was there that they ended up singing revolutionary songs with a Sinn Fein cell in the backrooms of the pub. Now of course this was during high political tensions in the country with the heavy hand of London bearing down on the Green Island in the Irish War of Independence (1919-21).

Lubin-Lebrère was promptly arrested and held in prison overnight. To the delight of the French XV, he was released hours before their game against Ireland where they recorded their first away win of French rugby history recording a 15-7 victory.

That was the figure of a man like Lubin-Lebrère. Of course the sporting world is drooling over the magic of Lionel Messi and rightly so, but can you imagine Messi or anyone else of the footballing entourage being blown to bits and left for dead on the Belgian killing fields only to jump up, brush himself off and stitch their name into national folklore. Only making a quick detour to the slammer as a pre-match ritual in typical Lubin-Lebrère fashion. You can hold your 10pm lights out and protein shakes – this was a proper sporting story.

As a spirited conclusion to this story - Lubin-Lebrère was partly responsible in getting the game of Rugby expelled from the Olympics for 92 years after he played against the USA at the 1924 Paris games. Where once the whistle blew on the 14-5 USA victory – the Olympic committee deemed it too violent for consideration thereafter.

A pretty fitting end to a sporting sport that was cast mostly away from the pitch.

Post a comment